This can be done by a custom service. Basic principle a sel-hosted service not on any application which serves as the login entry point for all registered apps i.e. active directory

Users typically need to work with multiple applications provided by, and hosted by different organizations with which they have a business relationship. However, these users may be forced to use specific (and different) credentials for each one. This can:

Users will, instead, typically expect to use the same credentials for these applications.

Implement an authentication mechanism that can use federated identity. Separating user authentication from the application code, and delegating authentication to a trusted identity provider, can considerably simplify development and allow users to authenticate using a wider range of identity providers (IdPs) while minimizing the administrative overhead. It also allows you to clearly decouple authentication from authorization.

The trusted identity providers may include corporate directories, on-premises federation services, other security token services (STSs) provided by business partners, or social identity providers that can authenticate users who have, for example, a Microsoft, Google, Yahoo!, or Facebook account.

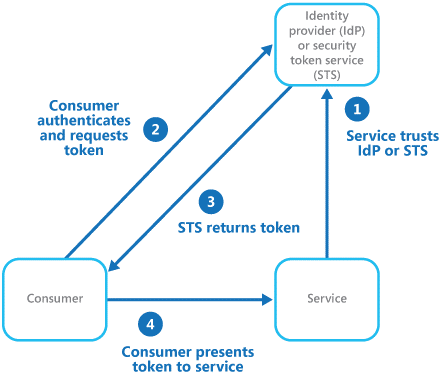

Above illustrates the principles of the federated identity pattern when a client application needs to access a service that requires authentication. The authentication is performed by an identity provider (IdP), which works in concert with a security token service (STS). The IdP issues security tokens that assert information about the authenticated user. This information, referred to as claims, includes the user’s identity, and may also include other information such as role membership and more granular access rights.

Figure 1 - An overview of federated authentication

This model is often referred to as claims-based access control. Applications and services authorize access to features and functionality based on the claims contained in the token. The service that requires authentication must trust the IdP. The client application contacts the IdP that performs the authentication. If the authentication is successful, the IdP returns a token containing the claims that identify the user to the STS (note that the IdP and STS may be the same service). The STS can transform and augment the claims in the token based on predefined rules, before returning it to the client. The client application can then pass this token to the service as proof of its identity.

This pattern is ideally suited for a range of scenarios, such as:

This pattern might not be suitable in the following situations: